Uses

Imageedit

Entropy coding originated in the 1940s with the introduction of Shannon–Fano coding, the basis for Huffman coding which was developed in 1950. Transform coding dates back to the late 1960s, with the introduction of fast Fourier transform (FFT) coding in 1968 and the Hadamard transform in 1969.

An important image compression technique is the discrete cosine transform (DCT), a technique developed in the early 1970s. DCT is the basis for JPEG, a lossy compression format which was introduced by the Joint Photographic Experts Group (JPEG) in 1992. JPEG greatly reduces the amount of data required to represent an image at the cost of a relatively small reduction in image quality and has become the most widely used image file format. Its highly efficient DCT-based compression algorithm was largely responsible for the wide proliferation of digital images and digital photos.

Lempel–Ziv–Welch (LZW) is a lossless compression algorithm developed in 1984. It is used in the GIF format, introduced in 1987. DEFLATE, a lossless compression algorithm specified in 1996, is used in the Portable Network Graphics (PNG) format.

Wavelet compression, the use of wavelets in image compression, began after the development of DCT coding. The JPEG 2000 standard was introduced in 2000. In contrast to the DCT algorithm used by the original JPEG format, JPEG 2000 instead uses discrete wavelet transform (DWT) algorithms. JPEG 2000 technology, which includes the Motion JPEG 2000 extension, was selected as the video coding standard for digital cinema in 2004.

Audioedit

Audio data compression, not to be confused with dynamic range compression, has the potential to reduce the transmission bandwidth and storage requirements of audio data. Audio compression algorithms are implemented in software as audio codecs. In both lossy and lossless compression, information redundancy is reduced, using methods such as coding, quantization discrete cosine transform and linear prediction to reduce the amount of information used to represent the uncompressed data.

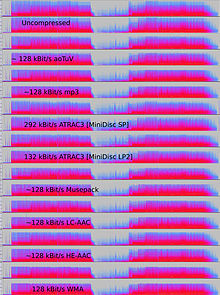

Lossy audio compression algorithms provide higher compression and are used in numerous audio applications including Vorbis and MP3. These algorithms almost all rely on psychoacoustics to eliminate or reduce fidelity of less audible sounds, thereby reducing the space required to store or transmit them.

The acceptable trade-off between loss of audio quality and transmission or storage size depends upon the application. For example, one 640 MB compact disc (CD) holds approximately one hour of uncompressed high fidelity music, less than 2 hours of music compressed losslessly, or 7 hours of music compressed in the MP3 format at a medium bit rate. A digital sound recorder can typically store around 200 hours of clearly intelligible speech in 640 MB.

Lossless audio compression produces a representation of digital data that can be decoded to an exact digital duplicate of the original. Compression ratios are around 50–60% of the original size, which is similar to those for generic lossless data compression. Lossless codecs use curve fitting or linear prediction as a basis for estimating the signal. Parameters describing the estimation and the difference between the estimation and the actual signal are coded separately.

A number of lossless audio compression formats exist. See list of lossless codecs for a listing. Some formats are associated with a distinct system, such as Direct Stream Transfer, used in Super Audio CD and Meridian Lossless Packing, used in DVD-Audio, Dolby TrueHD, Blu-ray and HD DVD.

Some audio file formats feature a combination of a lossy format and a lossless correction; this allows stripping the correction to easily obtain a lossy file. Such formats include MPEG-4 SLS (Scalable to Lossless), WavPack, and OptimFROG DualStream.

When audio files are to be processed, either by further compression or for editing, it is desirable to work from an unchanged original (uncompressed or losslessly compressed). Processing of a lossily compressed file for some purpose usually produces a final result inferior to the creation of the same compressed file from an uncompressed original. In addition to sound editing or mixing, lossless audio compression is often used for archival storage, or as master copies.

Lossy audio compressionedit

Lossy audio compression is used in a wide range of applications. In addition to standalone audio-only applications of file playback in MP3 players or computers, digitally compressed audio streams are used in most video DVDs, digital television, streaming media on the Internet, satellite and cable radio, and increasingly in terrestrial radio broadcasts. Lossy compression typically achieves far greater compression than lossless compression, by discarding less-critical data based on psychoacoustic optimizations.

Psychoacoustics recognizes that not all data in an audio stream can be perceived by the human auditory system. Most lossy compression reduces redundancy by first identifying perceptually irrelevant sounds, that is, sounds that are very hard to hear. Typical examples include high frequencies or sounds that occur at the same time as louder sounds. Those irrelevant sounds are coded with decreased accuracy or not at all.

Due to the nature of lossy algorithms, audio quality suffers a digital generation loss when a file is decompressed and recompressed. This makes lossy compression unsuitable for storing the intermediate results in professional audio engineering applications, such as sound editing and multitrack recording. However, lossy formats such as MP3 are very popular with end users as the file size is reduced to 5-20% of the original size and a megabyte can store about a minute's worth of music at adequate quality.

Coding methodsedit

To determine what information in an audio signal is perceptually irrelevant, most lossy compression algorithms use transforms such as the modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT) to convert time domain sampled waveforms into a transform domain, typically the frequency domain. Once transformed, component frequencies can be prioritized according to how audible they are. Audibility of spectral components is assessed using the absolute threshold of hearing and the principles of simultaneous masking—the phenomenon wherein a signal is masked by another signal separated by frequency—and, in some cases, temporal masking—where a signal is masked by another signal separated by time. Equal-loudness contours may also be used to weight the perceptual importance of components. Models of the human ear-brain combination incorporating such effects are often called psychoacoustic models.

Other types of lossy compressors, such as the linear predictive coding (LPC) used with speech, are source-based coders. LPC uses a model of the human vocal tract to analyze speech sounds and infer the parameters used by the model to produce them moment to moment. These changing parameters are transmitted or stored and used to drive another model in the decoder which reproduces the sound.

Lossy formats are often used for the distribution of streaming audio or interactive communication (such as in cell phone networks). In such applications, the data must be decompressed as the data flows, rather than after the entire data stream has been transmitted. Not all audio codecs can be used for streaming applications.

Latency results from the methods used to encode and decode the data. Some codecs will analyze a longer segment of the data to optimize efficiency, and then code it in a manner that requires a larger segment of data at one time to decode. (Often codecs create segments called a "frame" to create discrete data segments for encoding and decoding.) The inherent latency of the coding algorithm can be critical; for example, when there is a two-way transmission of data, such as with a telephone conversation, significant delays may seriously degrade the perceived quality.

In contrast to the speed of compression, which is proportional to the number of operations required by the algorithm, here latency refers to the number of samples that must be analysed before a block of audio is processed. In the minimum case, latency is zero samples (e.g., if the coder/decoder simply reduces the number of bits used to quantize the signal). Time domain algorithms such as LPC also often have low latencies, hence their popularity in speech coding for telephony. In algorithms such as MP3, however, a large number of samples have to be analyzed to implement a psychoacoustic model in the frequency domain, and latency is on the order of 23 ms (46 ms for two-way communication).

Speech encodingedit

Speech encoding is an important category of audio data compression. The perceptual models used to estimate what a human ear can hear are generally somewhat different from those used for music. The range of frequencies needed to convey the sounds of a human voice are normally far narrower than that needed for music, and the sound is normally less complex. As a result, speech can be encoded at high quality using a relatively low bit rate.

If the data to be compressed is analog (such as a voltage that varies with time), quantization is employed to digitize it into numbers (normally integers). This is referred to as analog-to-digital (A/D) conversion. If the integers generated by quantization are 8 bits each, then the entire range of the analog signal is divided into 256 intervals and all the signal values within an interval are quantized to the same number. If 16-bit integers are generated, then the range of the analog signal is divided into 65,536 intervals.

This relation illustrates the compromise between high resolution (a large number of analog intervals) and high compression (small integers generated). This application of quantization is used by several speech compression methods. This is accomplished, in general, by some combination of two approaches:

- Only encoding sounds that could be made by a single human voice.

- Throwing away more of the data in the signal—keeping just enough to reconstruct an "intelligible" voice rather than the full frequency range of human hearing.

Perhaps the earliest algorithms used in speech encoding (and audio data compression in general) were the A-law algorithm and the μ-law algorithm.

Historyedit

In 1950, Bell Labs filed the patent on differential pulse-code modulation (DPCM). Adaptive DPCM (ADPCM) was introduced by P. Cummiskey, Nikil S. Jayant and James L. Flanagan at Bell Labs in 1973.

Perceptual coding was first used for speech coding compression, with linear predictive coding (LPC). Initial concepts for LPC date back to the work of Fumitada Itakura (Nagoya University) and Shuzo Saito (Nippon Telegraph and Telephone) in 1966. During the 1970s, Bishnu S. Atal and Manfred R. Schroeder at Bell Labs developed a form of LPC called adaptive predictive coding (APC), a perceptual coding algorithm that exploited the masking properties of the human ear, followed in the early 1980s with the code-excited linear prediction (CELP) algorithm which achieved a significant compression ratio for its time. Perceptual coding is used by modern audio compression formats such as MP3 and AAC.

Discrete cosine transform (DCT), developed by Nasir Ahmed, T. Natarajan and K. R. Rao in 1974, provided the basis for the modified discrete cosine transform (MDCT) used by modern audio compression formats such as MP3 and AAC. MDCT was proposed by J. P. Princen, A. W. Johnson and A. B. Bradley in 1987, following earlier work by Princen and Bradley in 1986. The MDCT is used by modern audio compression formats such as Dolby Digital, MP3, and Advanced Audio Coding (AAC).

The world's first commercial broadcast automation audio compression system was developed by Oscar Bonello, an engineering professor at the University of Buenos Aires. In 1983, using the psychoacoustic principle of the masking of critical bands first published in 1967, he started developing a practical application based on the recently developed IBM PC computer, and the broadcast automation system was launched in 1987 under the name Audicom. Twenty years later, almost all the radio stations in the world were using similar technology manufactured by a number of companies.

A literature compendium for a large variety of audio coding systems was published in the IEEE's Journal on Selected Areas in Communications (JSAC), in February 1988. While there were some papers from before that time, this collection documented an entire variety of finished, working audio coders, nearly all of them using perceptual (i.e. masking) techniques and some kind of frequency analysis and back-end noiseless coding. Several of these papers remarked on the difficulty of obtaining good, clean digital audio for research purposes. Most, if not all, of the authors in the JSAC edition were also active in the MPEG-1 Audio committee, which created the MP3 format.

Videoedit

Video compression is a practical implementation of source coding in information theory. In practice, most video codecs are used alongside audio compression techniques to store the separate but complementary data streams as one combined package using so-called container formats.

Uncompressed video requires a very high data rate. Although lossless video compression codecs perform at a compression factor of 5 to 12, a typical H.264 lossy compression video has a compression factor between 20 and 200.

The two key video compression techniques used in video coding standards are the discrete cosine transform (DCT) and motion compensation (MC). Most video coding standards, such as the H.26x and MPEG formats, typically use motion-compensated DCT video coding (block motion compensation).

Encoding theoryedit

Video data may be represented as a series of still image frames. Such data usually contains abundant amounts of spatial and temporal redundancy. Video compression algorithms attempt to reduce redundancy and store information more compactly.

Most video compression formats and codecs exploit both spatial and temporal redundancy (e.g. through difference coding with motion compensation). Similarities can be encoded by only storing differences between e.g. temporally adjacent frames (inter-frame coding) or spatially adjacent pixels (intra-frame coding). Inter-frame compression (a temporal delta encoding) is one of the most powerful compression techniques. It (re)uses data from one or more earlier or later frames in a sequence to describe the current frame. Intra-frame coding, on the other hand, uses only data from within the current frame, effectively being still-image compression.

A class of specialized formats used in camcorders and video editing use less complex compression schemes that restrict their prediction techniques to intra-frame prediction.

Usually video compression additionally employs lossy compression techniques like quantization that reduce aspects of the source data that are (more or less) irrelevant to the human visual perception by exploiting perceptual features of human vision. For example, small differences in color are more difficult to perceive than are changes in brightness. Compression algorithms can average a color across these similar areas to reduce space, in a manner similar to those used in JPEG image compression. As in all lossy compression, there is a trade-off between video quality and bit rate, cost of processing the compression and decompression, and system requirements. Highly compressed video may present visible or distracting artifacts.

Other methods than the prevalent DCT-based transform formats, such as fractal compression, matching pursuit and the use of a discrete wavelet transform (DWT), have been the subject of some research, but are typically not used in practical products (except for the use of wavelet coding as still-image coders without motion compensation). Interest in fractal compression seems to be waning, due to recent theoretical analysis showing a comparative lack of effectiveness of such methods.

Inter-frame codingedit

Inter-frame coding works by comparing each frame in the video with the previous one. Individual frames of a video sequence are compared from one frame to the next, and the video compression codec sends only the differences to the reference frame. If the frame contains areas where nothing has moved, the system can simply issue a short command that copies that part of the previous frame into the next one. If sections of the frame move in a simple manner, the compressor can emit a (slightly longer) command that tells the decompressor to shift, rotate, lighten, or darken the copy. This longer command still remains much shorter than intraframe compression. Usually the encoder will also transmit a residue signal which describes the remaining more subtle differences to the reference imagery. Using entropy coding, these residue signals have a more compact representation than the full signal. In areas of video with more motion, the compression must encode more data to keep up with the larger number of pixels that are changing. Commonly during explosions, flames, flocks of animals, and in some panning shots, the high-frequency detail leads to quality decreases or to increases in the variable bitrate.

Hybrid block-based transform formatsedit

Today, nearly all commonly used video compression methods (e.g., those in standards approved by the ITU-T or ISO) share the same basic architecture that dates back to H.261 which was standardized in 1988 by the ITU-T. They mostly rely on the DCT, applied to rectangular blocks of neighboring pixels, and temporal prediction using motion vectors, as well as nowadays also an in-loop filtering step.

In the prediction stage, various deduplication and difference-coding techniques are applied that help decorrelate data and describe new data based on already transmitted data.

Then rectangular blocks of (residue) pixel data are transformed to the frequency domain to ease targeting irrelevant information in quantization and for some spatial redundancy reduction. The discrete cosine transform (DCT) that is widely used in this regard was introduced by N. Ahmed, T. Natarajan and K. R. Rao in 1974.

In the main lossy processing stage that data gets quantized in order to reduce information that is irrelevant to human visual perception.

In the last stage statistical redundancy gets largely eliminated by an entropy coder which often applies some form of arithmetic coding.

In an additional in-loop filtering stage various filters can be applied to the reconstructed image signal. By computing these filters also inside the encoding loop they can help compression because they can be applied to reference material before it gets used in the prediction process and they can be guided using the original signal. The most popular example are deblocking filters that blur out blocking artefacts from quantization discontinuities at transform block boundaries.

Historyedit

In 1967, A.H. Robinson and C. Cherry proposed a run-length encoding bandwidth compression scheme for the transmission of analog television signals. Discrete cosine transform (DCT), which is fundamental to modern video compression, was introduced by Nasir Ahmed, T. Natarajan and K. R. Rao in 1974.

H.261, which debuted in 1988, commercially introduced the prevalent basic architecture of video compression technology. It was the first video coding format based on DCT compression, which would subsequently become the standard for all of the major video coding formats that followed. H.261 was developed by a number of companies, including Hitachi, PictureTel, NTT, BT and Toshiba.

The most popular video coding standards used for codecs have been the MPEG standards. MPEG-1 was developed by the Motion Picture Experts Group (MPEG) in 1991, and it was designed to compress VHS-quality video. It was succeeded in 1994 by MPEG-2/H.262, which was developed by a number of companies, primarily Sony, Thomson and Mitsubishi Electric. MPEG-2 became the standard video format for DVD and SD digital television. In 1999, it was followed by MPEG-4/H.263, which was a major leap forward for video compression technology. It was developed by a number of companies, primarily Mitsubishi Electric, Hitachi and Panasonic.

The most widely used video coding format is H.264/MPEG-4 AVC. It was developed in 2003 by a number of organizations, primarily Panasonic, Godo Kaisha IP Bridge and LG Electronics. AVC commercially introduced the modern context-adaptive binary arithmetic coding (CABAC) and context-adaptive variable-length coding (CAVLC) algorithms. AVC is the main video encoding standard for Blu-ray Discs, and is widely used by streaming internet services such as YouTube, Netflix, Vimeo, and iTunes Store, web software such as Adobe Flash Player and Microsoft Silverlight, and various HDTV broadcasts over terrestrial and satellite television.

Geneticsedit

Genetics compression algorithms are the latest generation of lossless algorithms that compress data (typically sequences of nucleotides) using both conventional compression algorithms and genetic algorithms adapted to the specific datatype. In 2012, a team of scientists from Johns Hopkins University published a genetic compression algorithm that does not use a reference genome for compression. HAPZIPPER was tailored for HapMap data and achieves over 20-fold compression (95% reduction in file size), providing 2- to 4-fold better compression and in much faster time than the leading general-purpose compression utilities. For this, Chanda, Elhaik, and Bader introduced MAF based encoding (MAFE), which reduces the heterogeneity of the dataset by sorting SNPs by their minor allele frequency, thus homogenizing the dataset. Other algorithms in 2009 and 2013 (DNAZip and GenomeZip) have compression ratios of up to 1200-fold—allowing 6 billion basepair diploid human genomes to be stored in 2.5 megabytes (relative to a reference genome or averaged over many genomes). For a benchmark in genetics/genomics data compressors, see

Comments

Post a Comment